Calcium containing stones are the most common types of stones formed within the urinary tract. They are most commonly composed of a mixture of calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate. The etiology of calcium stone disease is diverse. In 15% of the patients, the condition is secondary to a known underlying disorder, the most common being primary hyperparathyroidism. Primary hyperparathyroidism accounts between 5% and 10% of the calcium stone forming population. Less commonly, in hyperoxaluria, hereditary hyperoxaluria, renal tubular acidosis, Cushing's syndrome, steroid treatment, Vitamin D intoxication, immobilization and medullary sponge kidney disease may be present. In the majority of patients, however, none of these disease processes are present and the stone disease is referred to as idiopathic or primary.

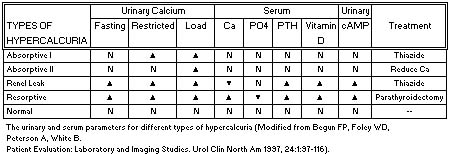

The majority of patients with calcium stone disease will demonstrate hypercalcuria (high calcium in the urine) which may be subdivided into one of three categories. These include absorptive hypercalcuria, renal hypercalcuria or resorptive hypercalcuria. Hypercalcuria can exist with or without hypercalcemia (high calcium in the blood).

The major factor in urolithiasis in children and adults is the production of insoluble calcium salts of oxalic acid. Hypercalciuria is the most common metabolic disorder associated with calcium oxalate stones, occurring in 30-60% of patients. Hypercalciuria is associated with a variety of metabolic disorders, including intestinal hyperabsorption (absorptive hypercalciuria), impaired renal calcium reabsorption (renal hypercalciuria) and increased skeletal demineralization (resorptive hypercalciuria). The urinary and blood chemistries that characterize these differing groups are summarized in the Table below.

Suggested readings

Rumi LA, Pearle MS, Pak CYC. Medical therapy: Calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:117-133.

Hyperoxaluria from various causes results in the deposition of insoluble calcium oxalate crystals in the kidney producing nephrocalcinosis and stone formation.

Primary (Inherited) Hyperoxaluria

Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (PH1) is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by a deficiency of alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT). In this condition, hepatic overproduction of oxalate occurs. The vast majority of families with PH1 show a horizontal autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Treatment should include pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) and magnesium supplementation as well as orthophosphate.

In primary hyperoxaluria, type 2 (PH2), there is a deficiency of the enzyme D-glycerate dehydrogenase/glyoxylate reductase. In contrast to PH1, in which patient's progress to end stage renal failure (ESRF) due to severe, bilateral nephrocalcinosis, patients with PH2 typically present with nephrolithiasis without ESRF. The treatment of PH2 is mainly supportive. Unlike the benefits seen with vitamin B6 therapy for the pyridoxine-sensitive patients with PH1, there is no effect in PH2 patients.

Suggested readings

Rumi LA, Pearle MS, Pak CYC. Medical therapy: Calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:117-133.

Hoppe B, Danpure CJ, Rumsby G, Fryer P, Jennings PR, Blau N, Schubiger G, Neuhaus T, Leumann E. A vertical (pseudodominant) pattern of inheritance in the autosomal recessive disease primary hyperoxaluria type 1: Lack of relationship between genotype, enzymic phenotype, and disease severity. Amer J Kidney Diseases 1007, 29: 1: 36-44.

Kemper MJ, Mullerwiefel DE. Nephrocalcinosis in a patient with primary hyperoxaluria type 2. Pediatr Nephrol 1996, 10:4:442-444.

Enteric Hyperoxaluria

Intestinal disease (malabsorption or short bowel syndrome) is the most common cause of hyperoxaluria. Reduced availability of free calcium to bind intestinal oxalate occurs in malabsorption. The colon absorbs unbound oxalate. Other putative mechanisms include increased colonic permeability and a decrease in Oxalobacter formigenes (oxalate-degrading bacteria. Treatment includes calcium citrate supplementation to bind intestinal oxalate and magnesium and Vitamin B6 supplementation.

Suggested readings

Rumi LA, Pearle MS, Pak CYC. Medical therapy: Calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:117-133.

Idiopathic Hyperoxaluria

In this group of patients, the hyperoxaluria is generally mild. Treatment consists of hydration and avoidance of foods containing. If a low oxalate diet with adequate calcium intake does not normalize urinary oxalate levels, Vitamin B6 may be added.

The increase oxalate excretion in very low birth weight infants (VLBW) is responsible for the high incidence of nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis in this group of patients. A spot urine for oxalate/creatinine ratio is suitable for screening VLBW infants.

Suggested readings

Rumi LA, Pearle MS, Pak CYC. Medical therapy: Calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:117-133.

Sonntag J, Schaub J. The identification of hyperoxaluria in very low-birthweight infants-Which urine sampling method? Pediatr Nephrol 1997, 11:2:205-207.

Cystine in the urine, or cystinuria, is a relatively rare autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism which is characterized by impaired reabsorption of dibasic amino acids (cystine, lysine, ornithine and arginine) from the renal tubules as well as the gastrointestinal tract. Only the basic amino acid, cystine, is associated with stone formation due to its poor solubility. Cystine stones represent 1 to 4% of all urinary calculi. The prevalence in the United States is 1 in 15,000 persons. It accounts for 6 to 8% of pediatric stones. Successful medical therapy in treatment of patients with cystine stones is based on three factors:

1. Decreasing total urinary cystine concentration

2. increasing the solubility of cystine

3. Decreasing urinary cystine excretion.

Successful medical management can be achieved by a combination of these therapeutic measures. This includes adequate fluid hydration and fluid diuresis. In addition, urinary alkalinization to a pH of 7.5 or higher with potassium citrate can decrease the solubility of cystinuria. In addition, D-penicillamine decreases the urinary excretion of cystine by binding cystine to form the more soluble cystine - S - penicillamine complex that is 50 times more soluble than cystine. However, numerous side effects including rash, fever, agranulocytosis, iron depletion, proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome have limited its use. Alpha-mercapto-propionyl-glycine, or Thiola, a newer agent with similar action to penicillamine, has fewer side effects.

Cystinuria, an autosomal recessive disease, results from excessive excretion of the four basic amino acids, cystine, ornithine, lysine, and arginine (COLA) into the urine. Cystine is relatively insoluble in acid urine. Patients with cystinuria (>250mg/24 hr.) produce a supersaturated urine and are at risk for crystallization and stone formation. The chemoprevention of cystine stones includes hydration and urinary alkalinization, cystine-binding agents (D-penicillamine, alphamercaptopropionylglycine, captopril), and irrigation chemolytic therapy (tromethamin E, acetylcysteine).

Suggested readings

Fitomer WL, Pak CYC. Recent advances in the biochemical and molecular biological basis of cystinuria. J Urol 1996, 156:6:1907-1912.

Rutchik SD, Resnick MI. Cystine calculi: Diagnosis and management. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:163-171.

Struvite stones, commonly called infectious stones, are composed of magnesium, ammonium and phosphate. Struvite stones represent 7-31% of all renal calculi. Struvite stones are produced from urease-containing bacteria (i.e., Proteus, Klebsiella). Multimodal therapy includes percutaneous nephrolithotomy possibly followed by extracorporeal lithotripsy and chemolysis. For very large stones, anatrophic nephrolithotomy is performed. Medical management with antimicrobial therapy, chemolysis (hemiacidrin), urease inhibition (acetohydroxamic acid) and urinary acidification helps to prevent stone recurrence.

Struvite or infection stones account for 15% - 20% of all renal calculi. They occur more commonly in females with a female to male ratio of 2:1. The stones are composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite) and carbonate apatite (calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate) and often obtain staghorn proportions. These stones are always associated with urinary tract infections with urease splitting bacteria (Proteus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus).

The indications for stone removal include urinary tract infection, progressive renal damage, urinary tract obstruction and persistent pain. Medical therapy is only an adjunctive roll in the management of these patients and is directed primarily at controlling the urinary tract infection prior to, during, and subsequent to surgical removal. Administration of Urease inhibitors (acetohydroxamic acid) may be useful in reducing the incidence of stone recurrence in patients with intractable urinary infections.

Suggested readings

Segura JW. Staghorn calculi. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:71-80.

Meretyk S, Gofrit ON, Gafni O, Pode D, Shapiro A, Verstandig A, Sasson T, Katz G, Landau EH. Complete staghorn calculi: Random prospective comparison between extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy monotherapy and combined with percutaneous nephrostolithotomy. J Urol 1997, 157:3:780-786.

Wang LP, Wong HY, Griffith DP. Treatment options in struvite stones. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:149-162.

These stones may result from a genetic disorder in patients who have an enzyme deficiency. They have a deficiency of the enzyme xanthine oxidase, which results in the production of xanthine and hypoxanthine rather than uric acid as an end product of purine metabolism. Urinary calculi occur in about a third of patients with this enzyme deficiency. These calculi may also develop in patients taking allopurinol, an xanthine-oxidase inhibitor. Pure xanthine stones are radiolucent, but approximately a third of patients with xanthinuria there may be a calcium salt mixture to render these stones slightly radio-opaque. These stones tend to be small, round or oval.

Suggested readings

Ogawa A, Watanabe K, Minejima N: Renal xanthine stone in Lesch-Nyhan syndrome treated with allopurinol. Urology 26:56, 1985.

This is an extremely uncommon metabolic condition in which a deficiency of the enzyme phosphoribosyl transferase (APRT) results in the conversion of adenine 2,8 -dyhydroxyadenine, a poorly soluble substance that readily crystallizes in urine. This results in DHA renal calculi, which have been identified primarily in children who would appear to have no other manifestations of their disease. Similar to uric acid stones they are radiolucent. However, unlike uric acid calculi, they are much more soluble in acidic pH than in an alkaline pH.

Suggested readings

Manyak MJ, Frensilli FJ, Miller HC: 2,8-Dyhydroxyadenine urolithiasis: Report of an adult case in the United States. J Urol 137:312, 1987.

Protease inhibitors are a new class of medication used to treat patients with HIV disease. Indinavir sulfate (Crixivan), a protease inhibitor, is widely used to treat patients with HIV infections. Urinary lithiasis has been associated with the use of Indinavir. As with other renal calculi, ureteral stents, hydration, analgesics, and antispasmodics have provided favorable outcomes. Nonsteroidal-anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) should be avoided as they have been shown to result in deterioration of renal function.

The formation of urinary lithiasis is a frequent complication of Indinavir therapy resulting in stones in 3-9% of patients. Hyperhydration and acidification of urine are usually successful. However, emergency drainage is usually required in 3% of cases. 20% of patients have been shown to have crystals in the urine. 8% of patients had urologic symptoms (3% had nephrolithiasis, 5% had crystalluria associated with dysuria/back pain). Crystalluria may be associated with dysuria and urinary frequency. Flank or back pain is associated with intrarenal sludging and the classic syndrome of renal colic. It is also believed that Crixivan stones may act as a nidus for heterogenous nucleation leading to the development of mixed urinary stones. Surgical intervention may be required in some patients. In addition, a combined medical and surgical intervention may be necessary. Indinavir therapy averaged 5.7 months prior to presentation of renal colic. All patients presented with microscopic hematuria. The median number of symptomatic urinary stone episodes after initiating Indinavir was 2 stones per patients. Radiographically, Indinavir stones are typically radiolucent. Abdominal CT scan demonstrated hydronephrosis without calcifications.

CT scan with contrast may demonstrate the presence of crixivan stones. These stones can cause high grade ureteral obstruction. The radiolucent-gelatinous nature of such stones makes lithotripsy a poor choice of treatment.

The incidence of uric acid calculi is approximately 5% - 10% of all renal stones. Men are affected four times more often than women. Approximately 25% of patients with gout will form uric acid stones. However, the majority of patients who form uric acid calculi have no detectable abnormalities in uric acid metabolism.

Factors that may contribute or predispose to uric acid stone formation include acidic or strongly concentrated urine, excess urinary excretion of uric acid, distal small bowel disease or resection (regional enteritis), ileostomies, myeloproliferative disorders being treated with chemotherapy and inadequate caloric or fluid intake. Treatment is tailored toward increasing urine volume and urinary pH. If hyperuricosuria is present, it can be corrected with appropriate dietary management and/or administration of allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor. Unlike most other renal calculi, existing uric acid stones can often be dissolved with either systemic or topical alkalinizing agents.

Facts

Occurrence: 3-15%

Produced in acidic urine (pH <5.5)

Radiolucent stones

Amenable to medical therapy

Medical History

Pathophysiological factors: anemia, neoplastic disorders, intoxication, cardiac infarction, irradiation and treatment with cytotoxic agents.

Metabolic abnormalities: primary gout, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome.

Pharmacologic influence on the excretion of uric acid: uricosuric agents (probenecid, sulfinpyrazone, salycilates), diuretics (thiazide, furosemide) and analgesics, vitamin C.

Treatment

In contrast to other types of stones, medical therapy is the mainstay of treatment and prophylaxis. Treatment includes hydration, and limitation of dietary sodium (<150 meq/day) and protein intake. Potassium citrate at a dose titrated to alkalinize the urine to a pH of 6-7 will dissolve uric acid stones.

Suggested readings

Low RK, Stoller ML. Uric acid-related nephrolithiasis. Urol Clin North Am 1997, 24:1:135-148.

Suggested readings

Teitel J. A side effect of protease inhibitors. [Comment. Letter] CMAJ 158(9): 1129-30, 1998. Clayman RV. Crystalluria and urinary tract abnormalities associated with indinavir. Journal of Urology. 160(2): 633, 1998.

Witte M. Tobon A. Gruenenfelder J. Goldfarb R. Cobum M. Anuria and acute renal failure resulting from indinavir sulfate induced nephrolithiasis. Journal of Urology. 159(2):498-9, 1998.

Kopp JB. Miller KD. Mican JA. Feuerstein IM. Vaughan E. Baker C. Pannell LK. Falloon J. Crystalluria and urinary tract abnormalities associated with indinavir [see comments]. [Journal Article] Annals of Internal Medicine. 12 7(2): 119-21199 7 Jul. 15.

Bruce RG. Munch LC. Hoven AD. Jerauld RS. Greenburg R. Porter WH. Rutter PW. Urolithiasis associated with the protease inhibitor indinavir. Urology. 50(4).?513?8, 1997.

Gentle DL. Stoller ML. Jarrett TW. Ward JF. Geib KS. Wood AF. Protease inhibitor?induced urolithiasis. Urology. 50(4):508?11, 1997. Bach MC. Godofsky EW. Indinavir nephrolithiasis in warm climates. [Letter] Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 14(3): 296? 7, 199 7.

Berns JS. Cohen RM. Silverman M. Tumer J. Acute renal failure due to indinavir crystalluria and nephrolithiasis: report of two cases. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 30(4):558?60, 1997.

Tashima KT. Horowitz JD. Rosen S. Indinavir nephropathy. [Letter] New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (2): 138-140, 1997.