ESWL

ESWL has been found to be the treatment of choice for treatment of stones less than 2 cm in diameter. The percentage of patients rendered stone-free following ESWL has varied from 47-96%, with a mean stone-free rate of 85%. Complications of ESWL include pulmonary damage (pulmonary edema and pulmonary contusion), skin bruising, and radiation exposure at the entry and exit sites of the shock waves.

The use of Styrofoam has become common practice in protecting the lung fields. Skin bruising may be partially preventable by protecting the exit site of the shockwaves with a 1-liter intravenous fluid bag placed on the abdomen. To avoid radiation exposure, the use of ultrasound to image the stone is a useful alternative.

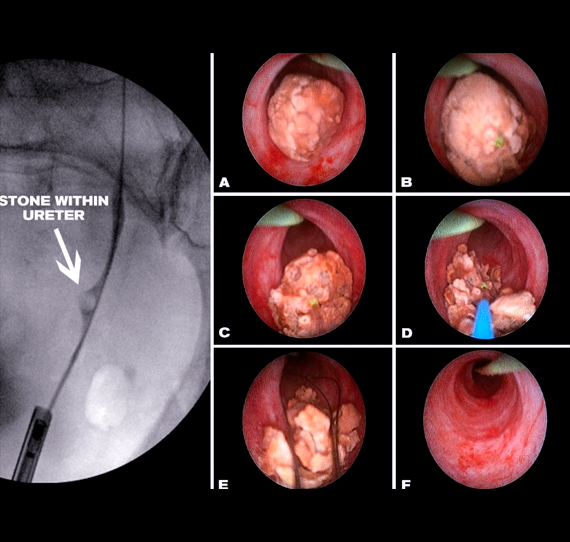

Ureteroscopy

Ureteroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure which involves placement of a small telescope within the ureter to gain access to the stone. There is no cutting or stitches required as in open surgery. Successful ureteroscopic stone extraction in children make ureteroscopy a useful technique.

The availability of smaller instruments and ureteroscopes makes this approach more feasible. Transurethral endoscopic access to the ureter and l pelvis of the kidney is now a routine procedure. Its limitation in children has always been the small size of the child’s ureter relative to the somewhat large size of the available instruments.

Newer ureteroscopes are available in sizes that make them suitable for many pediatric applications. Circon-ACMI has introduced a 6.9 Fr. two-channel ureteroscope through which small wires, baskets, and electrohydraulic probes may be used. A similar two-channel 6.3 Fr. instrument has been released by R. Wolf. These latter two instruments are progressively reinforced toward the eyepiece, so that even though the first 5 to 6 cm is small, the ureteroscope quickly increases in size.

This means that although the lower one third to one half of the pediatric ureter can often be entered and examined without ureteral dilation, attempts to further insert the instrument higher up the ureter may not be possible because of the increasing size of the ureteroscope.

In selected cases, ureteroscopy can be very useful in removing stones that might otherwise require a surgical procedure. Flexible baskets are advanced through the ureteroscope to engage or to grasp the stone and remove the stone without injury to the ureter. Otherwise, larger stones within the ureter can be broken by way of a laser fiber passed within the scope to fragment the stone into smaller pieces to be grasped by the basket as previously described.

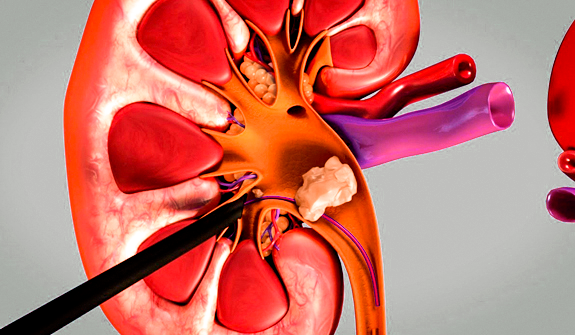

Percutaneous Lithotripsy

This procedure is utilized for patients with large stones (>2cm), stone refractory to ESWL or other treatments, and stones difficult to access (i.e., calyceal stones). Access to the kidney is achieved by insertion of a percutaneous nephrostomy tube, usually under fluoroscopic guidance. A tract is then dilated to a size sufficient to introduce a working instrument.

Once the tract is established, the nephroscope can be inserted. Inadvertent fluid absorption generating fluid overload may be the greatest risk. Other risk factors include bleeding and infection.

Most patients remain in the hospital for 2 to 4 days or occasionally longer, and disability is minimal.

Open Surgery

There are two clear indications for open stone surgery in the pediatric patient:

1. The treatment of stones occurring in congenitally obstructed systems such as ureteral pelvic junction obstruction (UPJO), or primary obstructed megaureter.

In this situation, correction of the congenital anomaly and stone removal should be performed simultaneously.

2. The treatment for complete staghorn calculus associated with infundibular stenosis. In order to achieve complete stone clearance and prevent stone recurrence, the infundibular stenosis must be corrected surgically.

As in the adult patient, some situations should be resolved by a standard open surgical procedure. Overall, the incidence of open surgery is small, between 2 to 4 per cent. Whether a given situation should be managed by an open surgical procedure is a matter of judgment. Many large stones, for example, cannot be removed by any reasonable number of shock waves (i.e., ESWL) or percutaneous operations. In these situations, the removal of stones are best managed by open surgery. When such a judgment is made, it must be remembered that open surgery will compromise the treatment of the patient’s next stone event, no matter how it is managed, because of the scar tissue resulting from the operation. This is a consideration of particular importance in children, who face a lifetime of risk of recurrent stone disease.